Dream Jobs Report

What makes us happy at work?

Overview

Work has always been one of the most important determinants of our happiness, but modern expectations for job satisfaction are higher than ever before — especially in technology. The good news? The majority of employed adults believe that it is possible to find their “dream” job — but only 4 in 10 say they already have. In an age of surging demand for technical skill sets, technology workers have more choice than ever before — so how do we explain the gap between dream job expectations and reality? To dig into that black box of job sentiment after the honeymoon period fades, Hired commissioned an online survey conducted by Harris Poll to survey 2,557 full-time employed adults aged 18 or older in the US, the UK, and Australia. The responses reflect that, although money continues to surface as the most influential driver of happiness in the workplace, it’s not the sole factor, and instead provide a more nuanced picture of what a dream job really looks like. Our findings reveal what factors are most crucial to happiness at work for people who love, hate, or feel iffy about their jobs, and offer insights for finding the right fit.

Is a dream job possible?

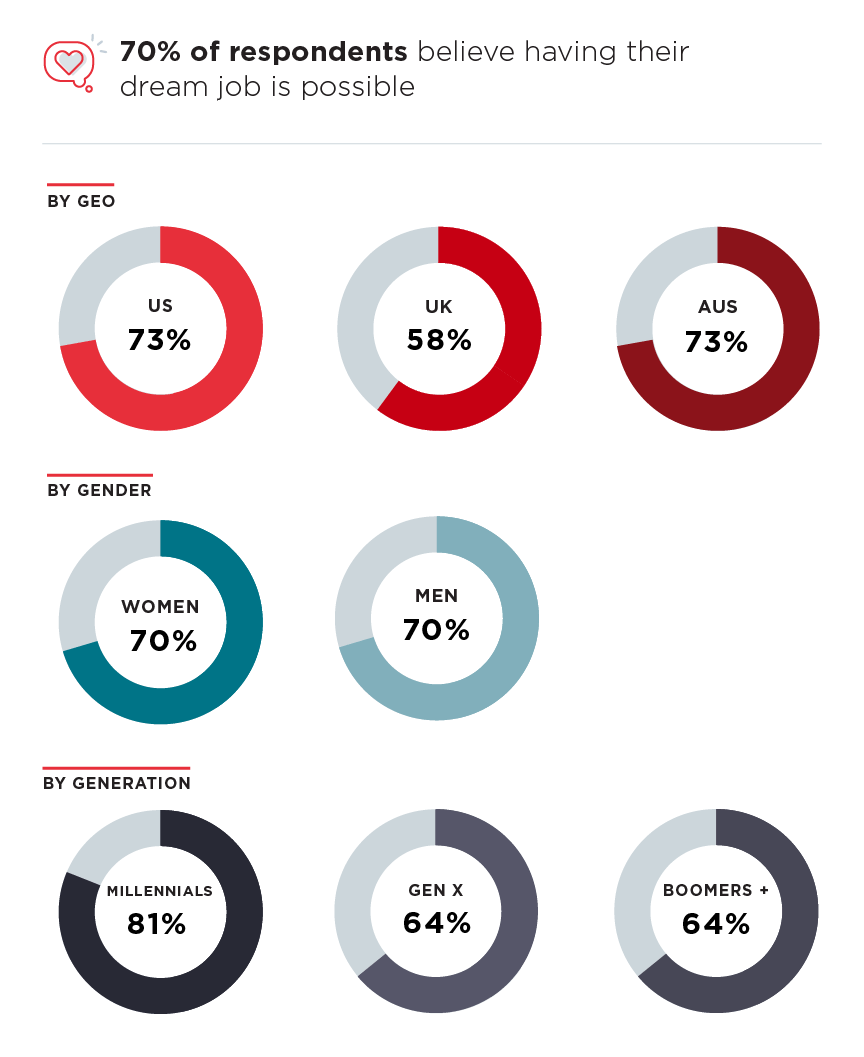

"The history of our psychological relationship with work, and its correlation to our happiness, is long and complicated. With the rise of Silicon Valley and its network of VC-funded rocket ships, so rose expectations for individual fulfillment through work: suddenly a job wasn’t just a job — it was a mission. People aren’t just building the latest apps and systems — they are purported to be changing the world — and with that, changing their perceptions of what professional success should look like and what value companies should provide back to their teams. As one of tech’s biggest powerhouses, Salesforce, puts it: "You deserve your #dreamjob." But how many people actually believe their dream jobs are possible? According to survey responses, a whopping 70% of employed adults believe having their dream job is possible. Despite the variety in salary levels, day-to-day experience, and availability of opportunities to the 2,557 individuals surveyed, optimistic sentiment about dream jobs remains high across all demographics — and disparities in hopefulness don’t emerge from the usual suspects. For example, our analysis shows that despite the unique challenges faced by women in tech, they remain equally bullish as their male counterparts on the possibility of finding their dream job. In fact, the biggest gaps in optimism emerge not between genders or between San Francisco and other metropolises, but between continents and generations."

For decades, Silicon Valley has been the epicenter of the tech industry, but that status is increasingly challenged by the rise of new technology and innovation hubs across the United States and around the world. In fact, our 2017 State of Tech Salaries report found that after adjusting for cost of living in San Francisco, cities like Austin, Melbourne, Seattle, and Toronto are increasingly attractive locations for tech workers to pursue their dream jobs. The idealization of working in tech is no longer relegated to the 30 miles in and around San Francisco — and the increase of high-value opportunities in other cities gives people hope that jobs meaningful beyond paying the bills are possible. Notably, belief in dream jobs is equally high in Australia as it is in the US — another indicator of Melbourne and Sydney’s increasing power of attraction as cities to jumpstart your career. In contrast, employed adults least likely to believe in dream jobs herald from the United Kingdom (58%), where our 2017 State of Salaries report also found salaries to be lowest when adjusted for cost of living. Our analysis shows that the majority of working adults believe finding their dream job is possible — and that it’s a great time to expand that search outside the bubble of the Silicon Valley.

Who has their dream job?

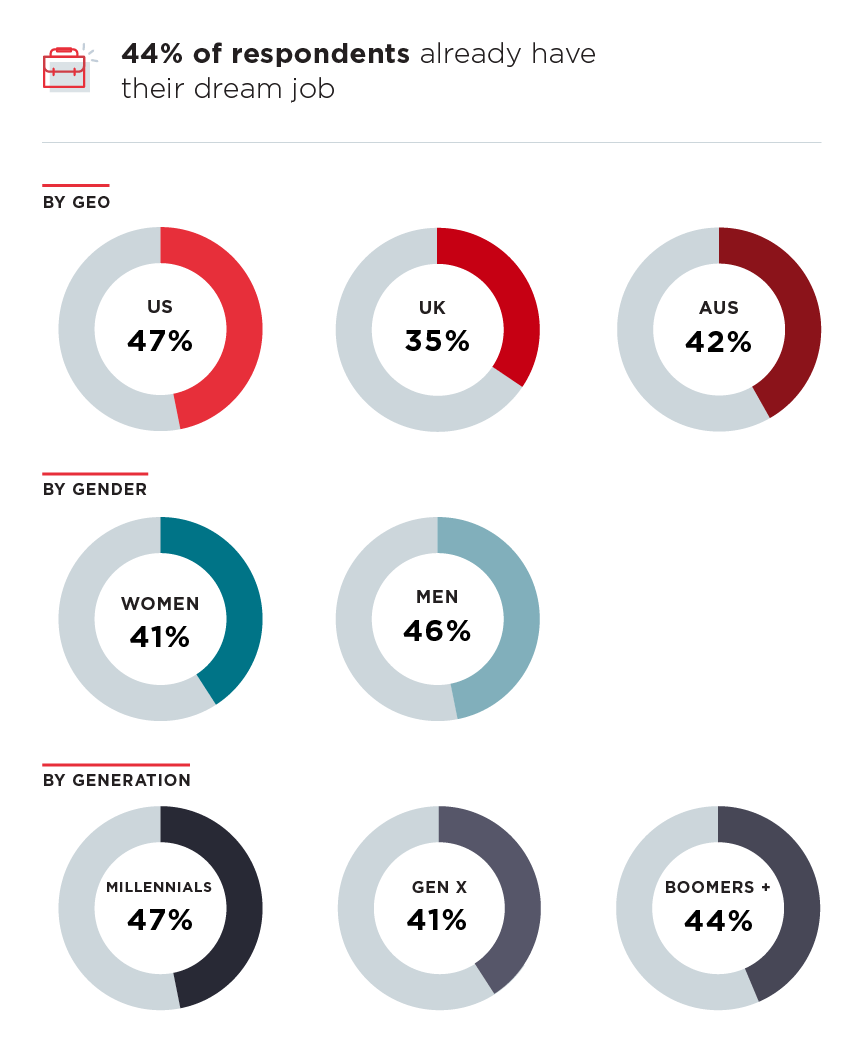

The majority of workers aspire to find their dream job, but who actually says they’ve found one? According to our survey, 4 in 10 respondents report they’ve already found their dream job. To avoid falling victim to the same Silicon Valley blinders Hired is working to overturn, it’s important to note that while the phenomenon of dream jobs is most prevalent in the technology sector (with 53% of respondents working in technology reporting they’ve already found their dream job), it is not unique to tech alone. Workers in healthcare, transportation, and education are similarly predisposed (at 52%, 49%, and 47% respectively) to perceiving their current role as a dream job, despite salaries that have remained more or less the same over the last few decades, per Bureau of Labor Statistics data analyzed by (Pew Research).

Male working adults in the US and Australia are most likely to report they already have their dream job (with 50% and 46% of respondents stating they somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement “I’ve already found my dream job”). Beyond this seemingly lucky category, however, gaps of expectation begin to appear: women slip behind men when it comes to reporting having found their dream job, with 40% of female respondents report they somewhat or strongly agree with the statement “I’ve already found my dream job”, compared to 46% of male respondents. Additionally, while the UK lags behind the US and Australia again by a 12% margin that corresponds neatly to the country’s optimism about dream jobs in the first place. These trends raise a poignant question about cause and correlation of career contentment: does believing in the possibility of a dream job affect your chances of actually landing one? Let’s take a closer look at dream jobs by generation. Employed Millennial respondents, perhaps not surprisingly, between the ages of 18 and 34, are 15% more likely than their Gen X and Baby Boomer peers to believe in the possibility of a dream job (at 81% for Millennials vs. 64% for Gen X and Boomers aged 52 and older). Although over 80% of Millennials report believing in the possibility of finding their dream job, only 47% report that they currently have one — the same proportion as their Baby Boomer peers, who never expected to have a dream job in the first place.

While there is no simple explanation for these gaps between expectation and reality, the trends are clear enough to encourage further conversation about what cultural and psychological factors are at play in the technology landscape. Perhaps in the UK, people are less hung up upon whether or not they have their dream job because they don’t expect the same level of fulfillment or personal satisfaction from work as Americans — and can rely upon a stronger social safety net if a job doesn’t work out. After all, people in Northern Europe have the highest scores of national happiness (according to Gallup and the UN’s 2016 World Happiness Report) in the world — whether they believe in dream jobs or not. Meanwhile, workers from Gen X and Baby Boomer generations may not expect fulfillment from their jobs because their lives are already full — or fuller, in comparison to Millennials who are pushing out traditional milestones like marriage and mortgages thanks to historical levels of debt and wage stagnation (per Pew Research’s report, Millennials in Adulthood).

People who love their jobs

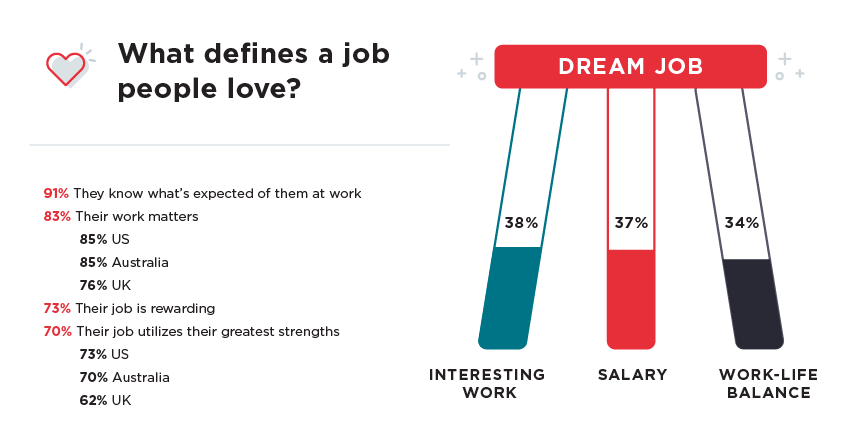

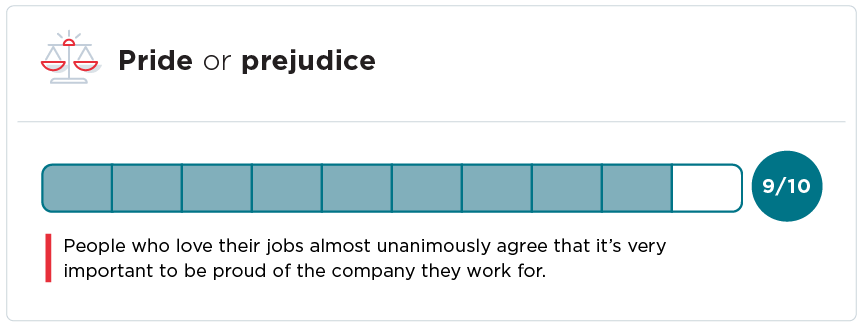

The gap between expectation and reality when it comes to dream jobs is wide enough to warrant a deeper dive into that lucky upper right quadrant: people who love their jobs. Our survey found that male respondents are more likely than female respondents to love their jobs, and workers in technology, healthcare, and engineering are most likely to feel good about what they do. For such people who believed in and sought after their dream jobs, what convinces them that they might finally have found it? To get to the heart of what makes people love their jobs, we asked respondents to select the factors most crucial to their happiness at work.

The ingredients of jobs well-loved by workers are fairly distributed, but revealing in and of themselves of a pervasive Silicon Valley culture: the weighted importance of work-life balance and salary is slightly edged out by the desire to be challenged and interested by the work itself. For many employed adults, it’s not enough just to take home a respectable paycheck and have time for family and hobbies. People who love their jobs ultimately feel like they can make an impact through their work — an opportunity that not all jobs might offer. Interestingly, our analysis shows that people who love their jobs are more likely to believe in the possibility of dream jobs in the first place. Almost 90% of working adults who love their jobs report that they believe having their dream job is possible, compared to just 62% for people whose job is “just okay” and 52% for those who say they hate their job. This gap might indicate something distinct about this type of working personality — perhaps an affinity for intellectual curiosity or gratification from work — that renders them more likely to view their work through a fundamentally positive lens. That being said, almost 1 in 2 people who love their jobs wouldn’t take a pay cut for anything, indicating that financial security and feeling valued is an integral part of a dream job.

People with mixed feelings about their jobs

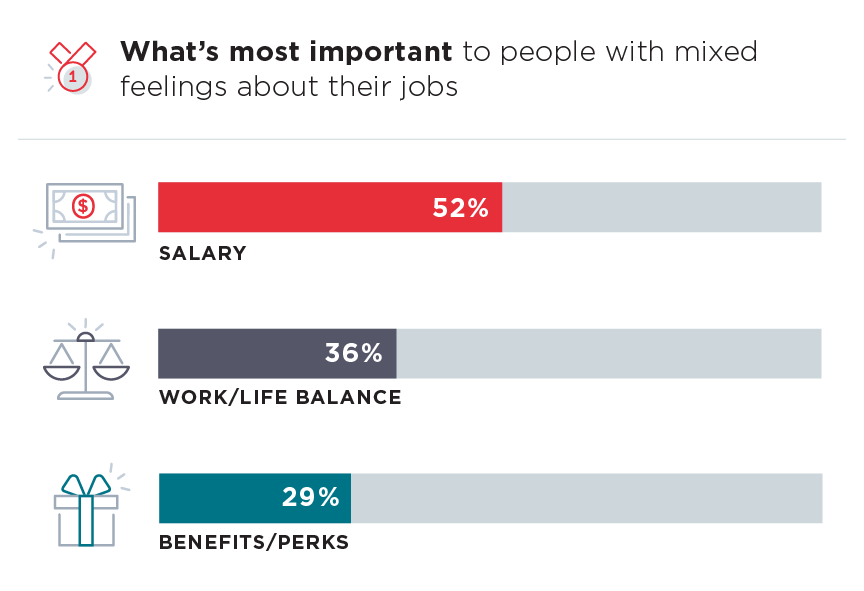

The good news: only 7% of respondents say they hate their jobs. But that leaves a majority (51%) of working adults on the fence about their job (and responded “just ok” to the survey question about how they feel about their current position). In fact, 42% of Americans say they daydream about leaving their current job at least once a month. Job loyalty thins beyond American borders, as working adults in the UK (41%) and Australia (39%) are more likely than those in the US (30%) to say they are actively looking for a job. Although sentiment amongst people who feel just okay about their jobs can vary widely, a couple of clear trends emerged from our data. First, 1 in 2 respondents who say their job is “just ok” report salary as one of the most crucial factors to their happiness at work. Second, work-life balance and benefits and perks weigh about equally as follow-up factors that could make a difference in this cohort’s attitudes toward their jobs.

According to our analysis of survey responses, people who feel generally iffy about their jobs tend to focus on extrinsic motivators — and this could be what differentiates their frame of reference for job satisfaction from people who report feeling happier at work. People who love their jobs were more likely to list intrinsic motivators, like feeling challenged or interested in their work, as the factors most important to their happiness at work.

Women on the fence

Women are less likely than men to say they love their jobs — but for many women stuck between loving and hating their current job (and report it’s “just ok”), pay is less of a factor than other job attributes when it comes to sticking with or leaving a position. For example, 66% of female respondents believe it is “very important” to find a job that allows them to do what they do best — and Millennial women in particular value a meaningful company mission over the prestige of the brand. Despite the gap between believing in and securing their dream job, however, (Gallup: Women in The Workplace). finds women still lead men on engagement as both individual contributors and managers — indicating that retention efforts for female employees may have the most positive ROI when it comes to productivity, turnover, and company profit.

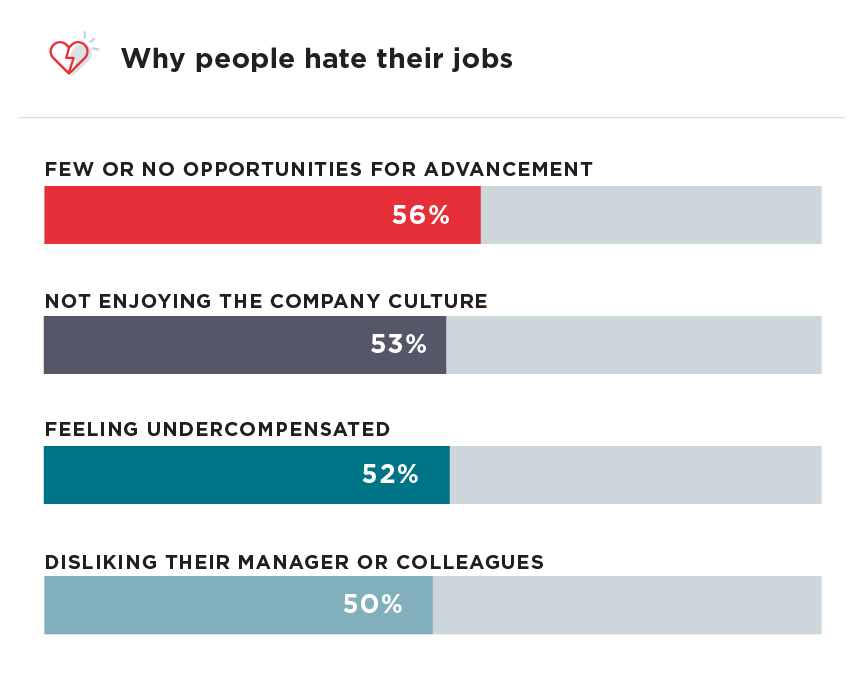

People who hate their jobs

Our analysis shows that loving or hating your job is rooted upon how you feel about your compensation. Once a worker feels good about how much money he or she makes, different factors seemingly become more important in evaluating what’s important about their job (like how interesting it is, or how good they feel about the company’s mission). If a worker doesn’t feel financially secure, it may not really matter what other great perks there are or how great their manager is. Nearly 3 in 4 employed adults who report hating their job say they stay in a job they hate because they need the financial stability — and 1 in 2 report that they left their most recent job because they were being underpaid. For employers and workers looking to address gaps in thought around compensation, it’s helpful to dive into the top reasons that workers report for disliking their job beyond salary — and evaluating what levers employers can pull to boost morale and job loyalty. Besides being underpaid, the most commonly cited grievances by people who hate their job include lack of opportunities for growth, a lackluster company culture, or not getting along with their manager or colleagues.

As expected, 6 in 10 respondents report that the #1 thing that would make them happier at work is more money. But beyond cold hard cash, workers report that improving company leadership (44%) and feeling like their work is more appreciated by their managers and colleagues (27%) would go a long way in improving their happiness at work. Our analysis shows that a worker’s attitude toward their job is neither exclusively financial, nor developed in a vacuum. Less tangible extrinsic motivators like increased visibility for a job well done or circumstances in workers’ personal lives all combine to shape our attitudes about work.

The lonely hearts club

Single people and people in the UK are twice as likely to hate their jobs. Meanwhile, the debate about whether or not Yoko affected John’s happiness at work rages on.

Conclusion

The data is clear: employees who believe dream jobs are possible are happier, and, as secondary research has found, happier employees are more productive. But perhaps because so many employed adults believe their dream job is possible, thoughts of greener grass are commonplace: more than a third of working adults are actively looking for a new job at any given moment, and more than 4 in 10 daydream monthly about it in the meantime. For employees who hate their jobs the most, retention is most likely to start with a conversation about salary and opportunities for learning and internal advancement. Meanwhile, in more mature markets, money alone might not be enough to keep talent: a strategic discernment of what motivates and satisfies employees are the next step to solidifying employee happiness. In the meantime, Hired believes everyone deserves a job they love — and is on a mission to make dream jobs a reality. Our analysis shows that the longer a worker spends looking for a job, the less likely they are to believe that dream jobs are possible; in fact, optimism drops 10% every 3 months that they spend on the hunt. We hope that by making the process of finding the right fit faster and more enjoyable for both companies and candidates, more people will have the chance to love what they do.

Methodology

The Hired Global Employment Study was performed in partnership with Harris Poll. The survey was conducted online by Harris Poll on behalf of Hired from September 26 to October 10, 2016. The research was conducted among 2,557 full-time employed adults aged 18 or older in the following countries: US (1,517), UK (518) and Australia (522). Data are weighted where necessary by gender, age, race/ethnicity, region, education, income, and propensity to be online to bring them in line with their actual proportions in the population.

About Hired

At Hired, we believe that fast-growing businesses need a better way to cut through the noise and find the talent who will help them fulfill their missions. We believe that top tech talent should have opportunities brought to their doorstep so that they can find the one that aligns with their lifestyle and will enable them do their best work. We’ve built a career matching platform that intelligently connects outstanding technology workers with the world’s most innovative companies. By taking the pain out of the job search, we want to empower everyone to find and do their best work, from one opportunity to the next. Hired is headquartered in San Francisco, with offices in cities across North America and Europe.